|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| In 1979, after returning from the Afrisa trip to Europe, Wemba began promoting the Sapeur ('Société Ambianceurs et Persons Élégants' thus 'SAPE' for short) as a youth cult specifically centred around Viva La Musica and its music. In Wemba's own words: "The Sapeur cult promoted high standards of personal cleanliness, hygiene and smart dress, to a whole generation of youth across Zaire. When I say well groomed, well shaven, well perfumed, it's a propriety that I am insisting on among the young. I don't care about their education, since education always comes first of all from the family. It's like, if you have children, it's up to you to raise and educate them. Outside of that, the children will get another education from those they associate with. Education is therefore always a truly personal experience that, above all, one gains from one's family". The Sapeur cult also caused much controversy, making Wemba a subject of debate and keeping him in the news for more than just his music. La SAPE drew its beginnings from the roots of the country's music industry way back in the late 1940s in a very socially 'unauthentic' manner. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

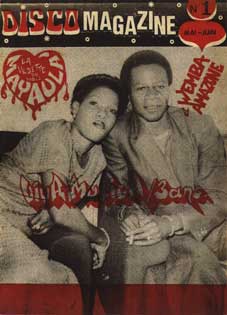

Disco Magazine Kinshasa 1980

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| In order to understand why, certainly we need to acknowledge the SAPE's Brazzaville based roots, but we also need to look back to the emerging Kinois music scene of the late 1940s and to the colonialist promotion of popular european fashion imports, including printed and waxed fabrics along with other items, aimed at 'upwardly mobile' urban African society. Music had assisted with the marketing of these goods. It had helped because the record company and recording studio owners were often also the owners of a local clothing boutique or general store outlet. With the company and studio owners looking to maximise their profits, many of the most popular musicians of the day were given 'free' clothing in the latest styles as part royalty payments on their compositions. Such 'gifts' would have been seen by fans who would then seek to purchase copies for themselves at the appropriate retail outlets. With Independence in 1960, and in the turbulent political climate of Zaire during the 1960s and early 1970s, all this changed. By 1974, Authenticity had lead to the banning of all european and western styles of imported clothing in favour of a return to the authentic Zaire. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| So Wemba introduced the Sapeur cult as a challenge to the dress code strictures imposed under Authenticity. He had visited Europe and he knew how Europeans lived. Papa Wemba wanted to reintroduce the condition that, to paraphrase, made it a pleasure rather than a crime to wear something from Paris. | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

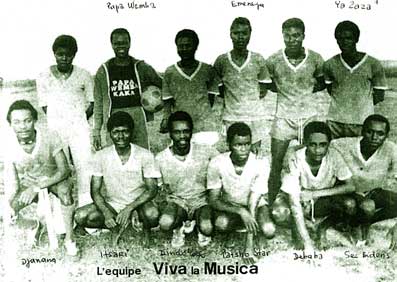

The Viva La Musica Football Team Kinshasa 1980 L-R: Papa Wemba, Emeneya, Ya Zaza, Djanana, Itshari, Dindo Yogo, Pacho Star, Debaba, Sec Bidens, |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Interviewed live on Zairian TV in 1981, Wemba was questioned about his latest outfit. He chatted with the interviewer, laughing off the interviewer's sarcasm. When questioned about his shoes, Wemba replied "Jimmy Weston™"; his trousers, "Tokio Kumagai™"; his jacket, "Armani™". Wemba shrugged off all criticism, remaining unflustered and stately to the last, much to the pleasure of the packed teenage studio audience. The Sapeur cult practically hoisted European haut couture designer fashions to the status of mock religion. The cult existed in absolute seriousness, held its own dances, and proclaimed its own manifestos and codes (such as defining ten ways of walking in order to show off one's couture clothes to their best degree). At times Viva's animateurs, Bipoli and Djanana, took showmanship to the limit of absurdity, stopping in the middle of a song to remove their shoes, placing a shoe on their heads and then resuming dancing where they had left off (supposedly so that the designer shoe could be admired without the distraction of movement). Viva's fans hung onto Papa Wemba's every word and certain among them held key positions such as 'high priest of kitende' (cloth), 'chancellor de la griffe' (griffe - designer label) and even 'le pape de kitende', because of their personal flamboyance and sizeable expensive wardrobes containing still officially banned non-Zairian suits and garments. Through both Viva La Musica's songs and dances, Papa Wemba ensured that references to expensive designer labels and styles proliferated at every opportunity, as he sought to drive trend-conscious Zairian teenagers away from other orchestras to become fans of Viva La Musica. Meanwhile the Mobutuist press kicked and screamed, declaring Wemba and his Sapeur cult 'bourgeois snobs', but this only served to popularise the cult further in the eyes of the younger generations of Zairian teenagers. At the same time as Wemba was challenging the confines of social Authenticity, he remained nonetheless absolutely true to Authenticity in a musical sense, doing much to promote Zaire's rich, tribal and folklore musical heritage. He spoke often about his own people's traditional musics and, since the beginning of Viva, he had always sung some of his hits in his tribal dialect (KiTetela), rather than in the national language of Lingala. During 'le règne de la SAPE' Wemba would also sometimes appear for Viva shows dressed in tribal costume, as a way of paying respect to his ancestors, before reverting to a designer suit for the following night's performance. As can be imagined, Papa Wemba attained huge success during this period, and a great many of his band's hits ('Mukaji Wanji', 'Ufukutanu' etc) increasingly drew from traditional folklore rhythms and melodies. Perhaps the most famous Wemba song of this period was the 1980 composition 'Ana Lengo', sung in the KiTetela dialect, which sold half a million copies Africa-wide. Following 'Ana Lengo', Viva La Musica held concerts playing to more than 50,000 people in both Kinshasa and Congo Brazzaville. Another Authenticity coup d'êtat Papa Wemba performed was recording with one of Zaire's earliest modern music stars, Antoine Wendo Kolosoi. Wendo had made a succession of hit 78s during the late 1940s and early 1950s and, until his rediscovery by Wemba, remained a forgotten favourite from the first generation of modern Congolese rumba music stars. In 1982 Wendo Kolosoi, Papa Wemba and Viva re-recorded the classic Wendo hits 'Efeka Mandundu' and 'Bato Ya Masuwa', one a lilting rumba and the other also a rumba until it eventually breaks into classic Viva mayhem during a scorching seben section. That same year, Wemba was also rewarded by his own tribe (Tetela) for his promotion of traditional music and culture. At a Viva concert shown live on national TV, he entered the arena carried on in a chair amidst a procession full of folklore bravado, spectacle and dance, fully dressed in warrior chieftain costume. A consecration ceremony followed and, in front of the TV viewing nation, it culminated with Wemba receiving the accolade of full Tetela warrior chieftain status from the clan's elders. Always in search of a larger wardrobe, by 1981 Wemba had become a frequent traveller to Europe. However, during Wemba's absences there were often problems within Viva and the first cracks began to show in September when four leading members of the band left to begin a new project. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

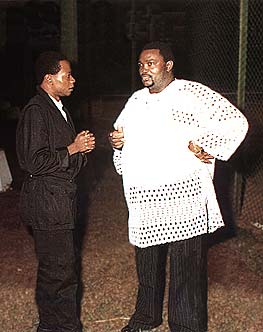

In spring 1982, soon after the collaboration with Wendo, Wemba decided to take another extended trip to Europe. He had already planned to use the trip to record solo (non Viva La Musica) material, backed by studio musicians who called themselves Les Djamuskets. The recordings were financed and marketed by Lluambo Makiadi, known as 'Franco', the long established leader of top Zairian orchestra, OK Jazz. By making these recordings, Wemba had now achieved the position of having worked with both of the country's top orchestra leaders, Tabu Ley and Franco. In doing so, he placed himself far above his contemporaries in stature. For any single artist to accomplish this was an unheard of feat, as Tabu Ley and Franco were deadly rivals who rarely helped promote an artist with whom either had previously worked. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Wemba & Le Grand Maitre Lluambo Makiadi AKA Franco | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

During Wemba's period away, the Viva musicians had been left to record their own compositions using the name Viva La Musica. Also, this time Wemba's absence had been longer than fans expected. Rumours abounded at home, some saying that Wemba was in jail and some that he had died. After his six-month trip, Wemba returned and was greeted at Kinshasa's N'djili airport by an entourage fit for Mobutu himself. The streets of Kinshasa were literally packed with people waiting to see the return of 'Le Kuru Yaka'. Wemba himself heard of the rumours in which he had featured so prominently and immediately entered the studios with Viva to record his reply, which was the song 'Événement'. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Today the truth is coming to light. In the faraway place where I happened to be, I was dead in prison. Today here I am come to life again. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Papa Wemba 1982. Editions Inza Inter. With thanks to Gary Stewart. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Alongside the song 'Événement' recorded on his return to Kinshasa, Papa Wemba also delivered the solo recordings made in Paris for Franco's VISA 1980 label. These were the songs 'Matebu' and 'Santa'. Still basking in his recent triumph, Wemba chose to ignore the rivalry between record labels and producers among the Kinois music industry. He had 'annoyed' a lot of people through his successful marketing ploys. Viva's members also became increasingly unsettled, having coped for so long in Wemba's absence. Eventually the break came and, in October 1982, ten of Viva La Musica's nineteen frontline musicians left the band to form a new orchestra called Victoria Eleison. |

|||||||||||||||||||||